I've just finished the book "Into the Wild" by Jon Krakauer. I saw the film and was impressed by the cinematography and story. Of course, the book delves deeper and tries to explore the rationale behind Chris McCandless's travels; his state of mind and beliefs and eventual death by starvation in the Alaskan wilderness.

I wasn't really too surprised that the book tried to defend what others call plain foolishness or folly especially as it was written by a fellow adventurer. McCandless was full of youthful bravado. He was idealistic and headstrong and some might say say foolish and naive. But he was also young, intelligent and fit. It's too easy to dismiss him as an idiot.

McCandless's idea was to walk into the Alaskan wilderness with minimal provisions and equipment and survive by living off the land. Perhaps something that many of us aspire to; but maybe not in Alaska!

The fact was that he didn't survive and nor did a myriad of others who have tried to do the same. Some of these excursions were also described in some detail in the book.

Rosellini summed up his failure in a letter to a friend before he committed suicide as reported by Krakauer:

" I began my adult life with the hypothesis that it would be possible to become a Stone Age native... I learned that it is not possible for human beings as we know them to live off the land." [p76]

So why are these extended, lonely excursions into the wilderness doomed to failure and could we, with our knowledge of bushcraft and survival, do any better?

I expect a few reading this would say that they would prepare themselves better and that they would ensure that they have the requisite knowledge and skills to deal with the conditions they would undoubtedly encounter. They might say, "I've done the course, got the T-Shirt" and "survived" with just billy and blanket. As a minimum, we would at least take some emergency equipment. After all, McCandless didn't even bother with a map. He learnt no skills prior to his adventure, except for a bit of game prep. Instead he decided to learn "on the hoof" from books taken into the wilderness with him.

But are even the most experienced and skilled bushcrafters or survivalists just kidding themselves when it comes to true survival and living in the wilderness? A behind the scenes look at a Survivorman episode shows how much preparation goes into a trip. Despite the one-man presentation in a seemingly empty wilderness, locations are carefully selected and skills are learnt from a local survival expert just days before he walks in.

I suggest that survival situations are impossible to replicate. A week long course may give you a few ideas (for that particular environment) but would that be enough?

I don't believe knowledge and skills are enough. It has to be something more. In fact I consider that it's two factors. Firstly, there must be a will to survive; not just to get by and live off the land for a short time, but to actually live and survive long term (in fact shouldn't the words "live" and "survive" be used synonymously?)

Contrary to the film and book, it has been shown that there were no toxins in McCandless's body, therefore the fact that his starvation was blamed on misidentification of a plant and eating the poisonous seed pods from that plant is probably not correct. In my mind this is perhaps an excuse to blame his naivity for his death.

I believe McCandless just gave up. This isn't hard to do and anyone who has been in even a vaguely similar situation might know what I mean. I'm not an expert on survival physiology or psychology by any means but I have been an expedition leader and I have seen and experienced this syndrome. Even mild exposure in the UK's lowland hills will cause the victim to curl up in a ball while the body attempts to shut down some essential systems. If you multiply this by prolonged failure to find proper nourishment and a prolonged state of solitude in a place like Alaska, it won't be long before the body and more significantly the mind starts to give up and eventually fail.

It's not easy to recover from the downward spiral of demotivation. I'm not suggesting McCandless committed suicide (and the book goes to great lengths to dismiss these suggestions.) McCandless in fact had made up his mind to walk out; he'd had enough but then so did Rosellini. But by then it was all too late. Put up what looks to be like an impenetrable barrier (in McCandless's case it was a swollen river) and it would seem like the end of the world. He, like Rosellini, had reached the point of no return.

Examples of successful survival in extreme cases are well documented and the most successful psychological strategy has apparently been built firmly on a will, a motivation or a need to survive - an aim, a focus, a love, a family at home, a determination not to fail. McCandless had none of these or at least thought he didn't and this slowly eroded away his determination to succeed.

This brings me to the second contributing factor as to why extended wilderness living fails. This is solitude. I've often questioned the rule of three's where the final "three" is the sweeping statement that you can't survive more than three months without human contact. Perhaps a little extreme but there must be a basis for it. I'm sure many of us dream of living in the wilderness alone with the minimum of kit as did McCandless. But this dream is of course nonsense. Human contact and belonging is a basic human requirement, if not in the short term, then definitely long term. Sure, there have been some examples of people living alone but these are few and far between.

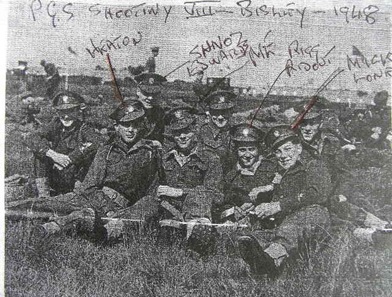

Even disregarding the psychological aspects of lack of human contact and the basic human survival requirement of belonging, there's also an obvious practical aspect. We have previously survived in the wilderness as part of a tribe or clan or family. We worked together, formed hunting parties, shared tasks and split our daily workload and chores, built communities and relied on each other.

Whether they had the skills or not, McCandless and the others lived out the dream of solitude. Perhaps this was their demise. Perhaps we shouldn't make it ours.

Pablo.

![STA71304[1]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/prmaklpboo/SJ6mEBlwwuI/AAAAAAAAB3Y/VfaHP04QSfQ/STA71304%5B1%5D_thumb%5B4%5D.jpg)